THIS IS NOT INVESTMENT ADVICE. INVESTING IS RISKY AND OFTEN PAINFUL. DO YOUR OWN RESEARCH.

The Board just sits there and watches…we should be paying 1% Interest, or better! – President Trump

While the White House has successfully coerced smaller trading partners, universities, members of Congress, law firms, vaccine specialists and others to comply with its directives, it has been less effective against stronger adversaries like China and the bond market. People instinctively resist coercion, if they have the leverage to do so. A critical battleground in this struggle is the U.S. dollar. For the dollar to maintain its current value, the U.S. must attract approximately $1.3 trillion annually from global savers. From the perspective of an asset allocator in Europe or Asia, the logical response to erratic US policy is to reduce dollar exposure, especially given concerns about the Federal Reserve’s diminishing independence.

Coercion

Political coercion is not new. This weekend’s U.S. holiday commemorates the end of coercive British rule. Over the past 50 years, a defining geopolitical shift has been the dissolution of the Soviet Union—a coercive union—and the rise of the European Union, a voluntary one. The Soviet Union relied on significant physical and psychological coercion to control its members. People risked their lives to escape. In contrast, despite its bureaucratic inefficiencies, the European Union attracts nations willing to make substantial sacrifices to join. Ukrainians are risking and losing their lives to do just that.

The US miracle is that people voluntarily supported the experiment. No one forced people to scale the Berlin Wall or sprint through North Korea’s DMZ or clamber through Laos to escape China. They were drawn to America.

The White House’s current policy leans heavily on force, rather than persuasion by example. Instead of fostering a business and regulatory environment that naturally attracts investment, tariffs force companies to relocate production. This coercive approach extends to policies targeting universities, protests, tax and health policy. Grift is on the upswing. Critically for investors, the White House is pressuring the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates despite little economic justification, and it is likely to replace the current chair with a more pliant supporter when Powell’s term ends in May.

The Dollar

Global investors have voluntarily plowed their savings in the U.S. When I lived in Russia, the currency of choice among mobsters was crisp $100 bills. The table below ranks countries by their current account deficit as a percentage of GDP, a straightforward measure of a nation’s spending versus savings. Countries like the U.S., which spend more than they earn, rely on borrowing from nations with surplus savings, a transaction that then prices the exchange rate. The trade deficit is one component of the current account deficit. While smaller economies like New Zealand have larger deficits relative to GDP, the sheer size of the U.S. economy means it requires significantly more capital to fund its deficit.

To date, financing the U.S. current account deficit has been manageable. The dominance of U.S.-based tech companies for instance has attracted significant capital inflows, bolstered by the perception of the U.S. as possessing a stable and predictable regulatory environment. However, this dynamic is shifting. Specifically:

a) The U.S. has substantial financing needs in dollar terms relative to history

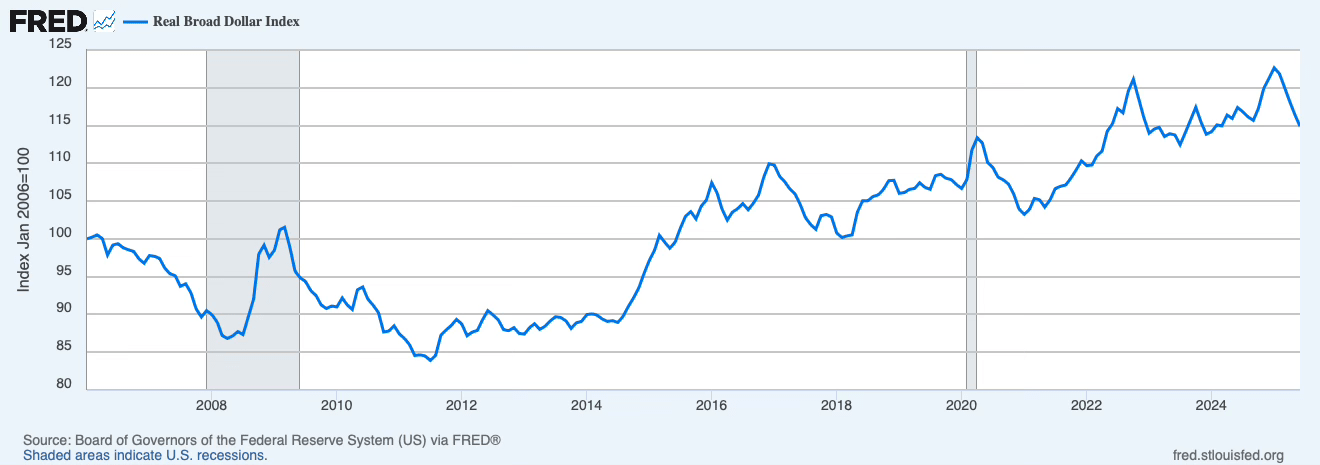

b) The dollar is historically expensive relative to other currencies

c) Hedged returns for foreign investors holding dollar-denominated assets are negative

d) The White House is undermining the Federal Reserve’s independence

To be sure, markets are never easy. It’s possible that the US economy turns out to be stronger than expected, Powell doesn’t cut rates and this relative tightness supports the dollar until his term expires. That said, the odds of this seem low.

Beyond signs suggesting some moderation in economic growth, the chart below provides additional context: the U.S. current account deficit is among the widest it has ever been. Reducing the trade deficit also means reducing capital inflows.

By traditional measures, the dollar is quite expensive, as you can see below, when measured in real terms and, as I noted above, the hedged return of owning dollar assets for many foreigners is negative.

Beyond the decline in the dollar’s value so far this year, concrete evidence of a broader funding crisis is scarce. We know tourism to the U.S. has noticeably decreased, signaling reduced foreign engagement. However, the private hedging decisions of major corporations and asset managers remain opaque. It’s unclear how much of the dollar’s decline is driven by speculators.

Early in my Wall Street career, I advised corporations on managing exchange rate risks. Their hedging decisions were rarely disclosed publicly, though some details occasionally appeared in 10-K filings. Given the lack of transparent data, investors today must make forward looking decisions with limited information. If foreign holders of U.S. assets perceive even a modest risk of the Federal Reserve losing its independence, it seems logical to increase hedging now or reduce their U.S. asset purchases to get ahead of a more violent dislocation. Like I said at the outset, the White House can’t force these savers to put their money in the US.

Now out in Korean, Italian, Estonian, Chinese and many other languages:

The Uncomfortable Truth About Money