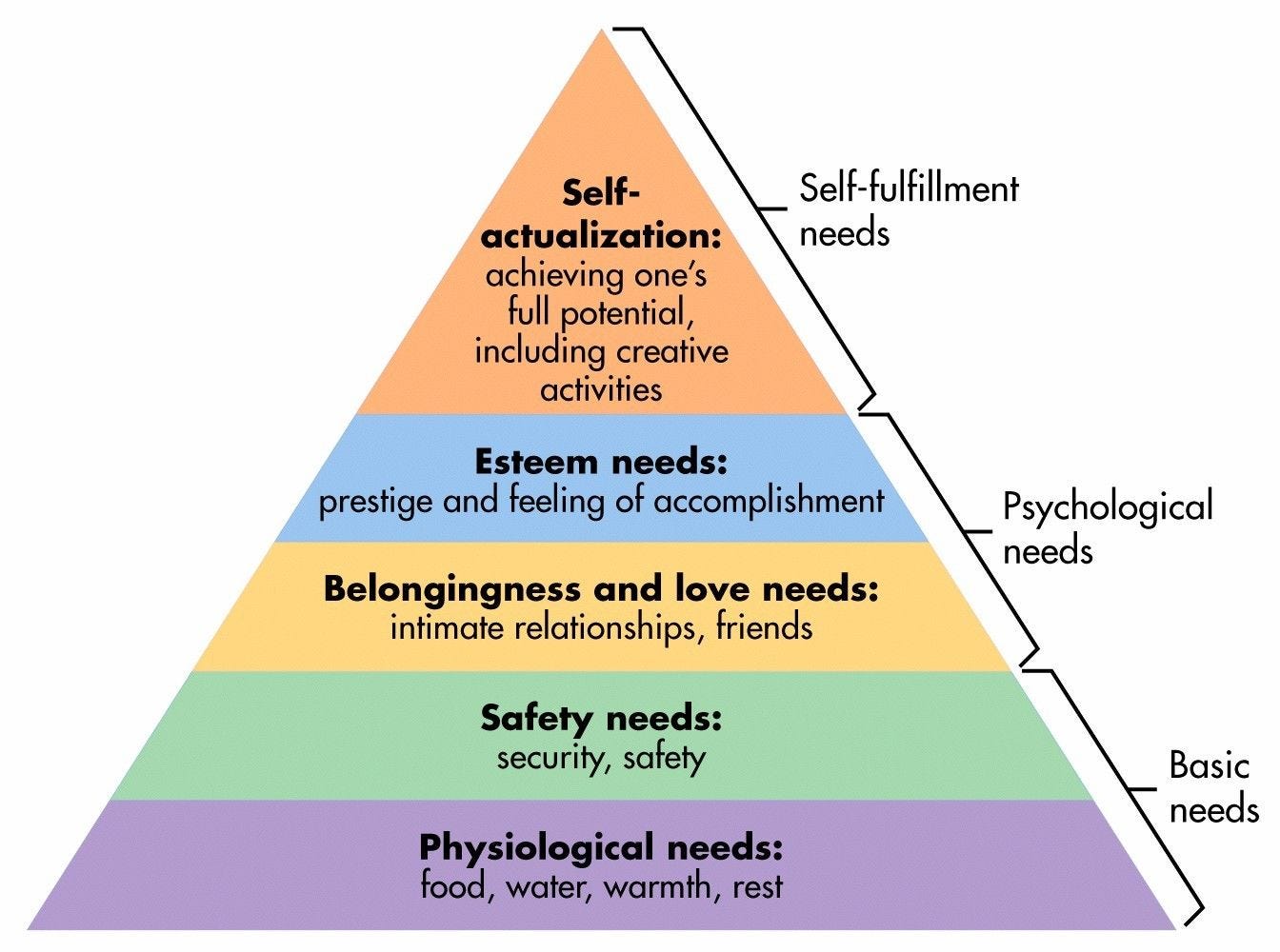

“In any given moment we have two options: to step forward into growth or to step back into safety.” Abraham Maslow (1908-1970), creator of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

On Maslow’s growth path toward what he termed “self-actualization” we face immoveable objects. Everyone bumps into different obstacles, but we all encounter them. They either are unsurmountable or we figure out how to go around them. In today’s post, I want to share some immoveable objects I’ve encountered. In each case, what I initially deemed to be a detour turned out to be the growth path. Is that universal or just idiosyncratic experience? I’d be curious to hear about meaningful detours you may have taken; perhaps I can combine them into a follow-up post.

Source: Simply Psychology

What’s true of individuals is I suspect true of groups. The vomit-encrusted infant’s crib upends family peace but also creates a focus and shared experience. The family can get stronger when it makes it through a disruption. Similarly, Ukraine’s war is an awful, bloody detour from the path to modernity. But it is in the detour that Ukraine as a nation appears to have coalesced. Economic crises—pandemic, 2008 credit crisis, 2001 tech wreck, etc.—may do the same thing. Below a discussion of three barriers I’ve encountered and then the how to pay for it section.

Entrepreneurship

In 2020, I quit the corporate world, a track I’d been on for 20+ years. My goal was to write great stories and grow, consistent with Maslow’s prediction. I was 52, an age when a truly immovable obstacle—death—no longer felt distant. Losing my salary and a community was unnerving; so was the possibility of feeling my growth atrophy.

At the outset, my expectations were not specific. To publish a book simply required writing one and then finding both agent and publisher, right? I’d heard of others getting a “publishing deal” and was intrigued and hopeful. I pictured (embarrassing to admit) days banging out stories from exotic locations (picture Hemingway in Cuba) interrupted by appearances at book festivals. Nice gig, right?

Bam! I hit an unmovable object. No book agent would take me on. With book #1, one agent said they “would not represent a book that is going to scare the shit out of people about adoption.” With book #2, an eery silence. Is book #2 bleh or was writing about China too risky for the five mega publishers? I’ll soon find out.

Still Press was my path around. Two-years on, 4k+ copies of Raising a Thief have been sold in English and I’m not sure how many copies sold in Chinese and Turkish translations. Most people like the book, 15% hate it. I must do everything a publisher does—proofread, legal, graphic, marketing, foreign rights, film adaptions, admin, tax, etc. and I can’t do it alone. Still Press is a store, like the one below. It isn’t Hemingway in Cuba yet the people who have joined me are exceptional and, hopefully, some of the content gives you joy and meaning. What seemed a detour is now the thing itself.

Photo: Paul Fetters

Fatherhood

“I’m pregnant,” said my wife, Marina. It was 1993. She was then my girlfriend. We had recently moved together in Moscow, a story I detailed in book #1. Up until that point, she had thought she was infertile. Oops.

What followed was one child, then a second. Like many young families, starting out we had no money. We first lived across the street from a car-repossession lot with a snarly dog. But I pictured a bright future. It looked something like four kids, a black lab on a wrap around porch and reading aloud after dinner.

Bam! I ran into another unmovable object. My kids are each incredible human beings and they were not easy to raise, a challenge I’ve described before and won’t repeat here. As the parenting challenges ramped up, my marriage, finances and career came under intense pressure.

To get around the immovable object, I had to abandon one career (foreign correspondent) for another (investor), hire a great marriage counselor, navigate two corporate mergers and countless bosses, some of whom were wonderful and others who were … a challenge. Fatherhood was not what I expected but, like for many parents, the most meaningful work I’ve done.

Learning Russian

In the fall of 1983, in a white cinder block building, I took a course in Russian history and culture at my Washington, D.C. high school. My teacher, Barbara Davis, introduced me to Russian literature. Given that Russian books are long and the attention of teen-agers short, she selected chapters like The Grand Inquisitor, from Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov.

The story was unlike anything else I had read. (“Thou didst promise them the bread of Heaven, but I repeat again, can it compare with earthly bread in the eyes of the weak, ever sinful and ignoble race of man?”) That’s it, the impulsive teenage me decided, I have to see Russia and learn Russian! At the time Russia was the Soviet Union, like North Korea but with much more scale.

Whack! Another immovable object. In college, learning Russian was hard for many and brutal for me. I discovered I had mild dyslexia. In a class of 20+ students, I was dead last, fat slices of humble pie day after day. I barely passed, then moved to Moscow after school, where I met my wife and started a family. In the ensuing thirty years I read a lot of books in Russian. Initially I needed to look up every word. Below is The Brothers K in Russian.

What’s the point of all this? I think that the twists and turns have as much or more meaning as the straight and narrow.

How To Pay For It

Safety is the second rung on Maslow’s triangle and for me and likely for you money is a key part of that. One of my “detours” turned out to be a lot of time on Wall Street and I try to channel all of that learning into these posts and my own money management. Writing may or may not pay so money management is critical.