“With liquidity like it is, it’s crazy not to get funding.”

I was sitting on an unsteady metal stool drinking coffee on the lower East Side of Manhattan. The sun was finally out. Opposite me was a 30-something software entrepreneur whose start-up was already cash-flow positive. But why not turbo-charge it with funding?

In the short-term, the economy is accelerating. You can see it. The road traffic is thicker. The shelves at the grocery store—empty at pandemic peak—are full. And you can see it in the data. Economists estimate that the economy will grow 6% this year. Inflation is above 4%.

In the medium-term, something more substantial is afoot: companies are dying. Companies are always dying, the only question is the rate at which it is happening. Given both the disruptive nature of today’s technology and the ease with which one can get funding, this death rate will likely accelerate, both from existing companies dying and junky companies being created on cheap money. This corporate life cycle impacts each of us.

Dropping Out

Apple is a key component of stock index averages, like the Dow and the S&P 500. It is valued, today, at roughly $2 trillion. I love the company. I am writing this on an Apple computer and wearing an Apple watch. And yet I know it will die. I just don’t know when and exactly how.

One perspective on this cycle of corporate life is to see who is in the major stock market indexes over time. This is inexact because the criteria for who gets in and out is technical and a company can still be very much alive yet fall from the index. Still, I find the perspective helpful. Today the members of the Dow Jones Industrial Average are familiar names––in addition to Apple, companies like American Express, Coca-Cola, Intel, JP Morgan.

If you go back roughly 50 years, it’s a different set of names––American Tobacco, Eastman Kodak, General Motors, Sears Roebuck and United States Steel. Go back 50 years before that, to 1920. The top companies include American Locomotive, American Sugar, Central Leather Company and Western Union. In the 19th century, the top companies include American Cotton Oil, Chicago Gas and Light, Tennessee Coal and United States Rubber. (After showing a draft of this piece to an early reader, they forwarded me a clip of Buffet noting some of these shifts).

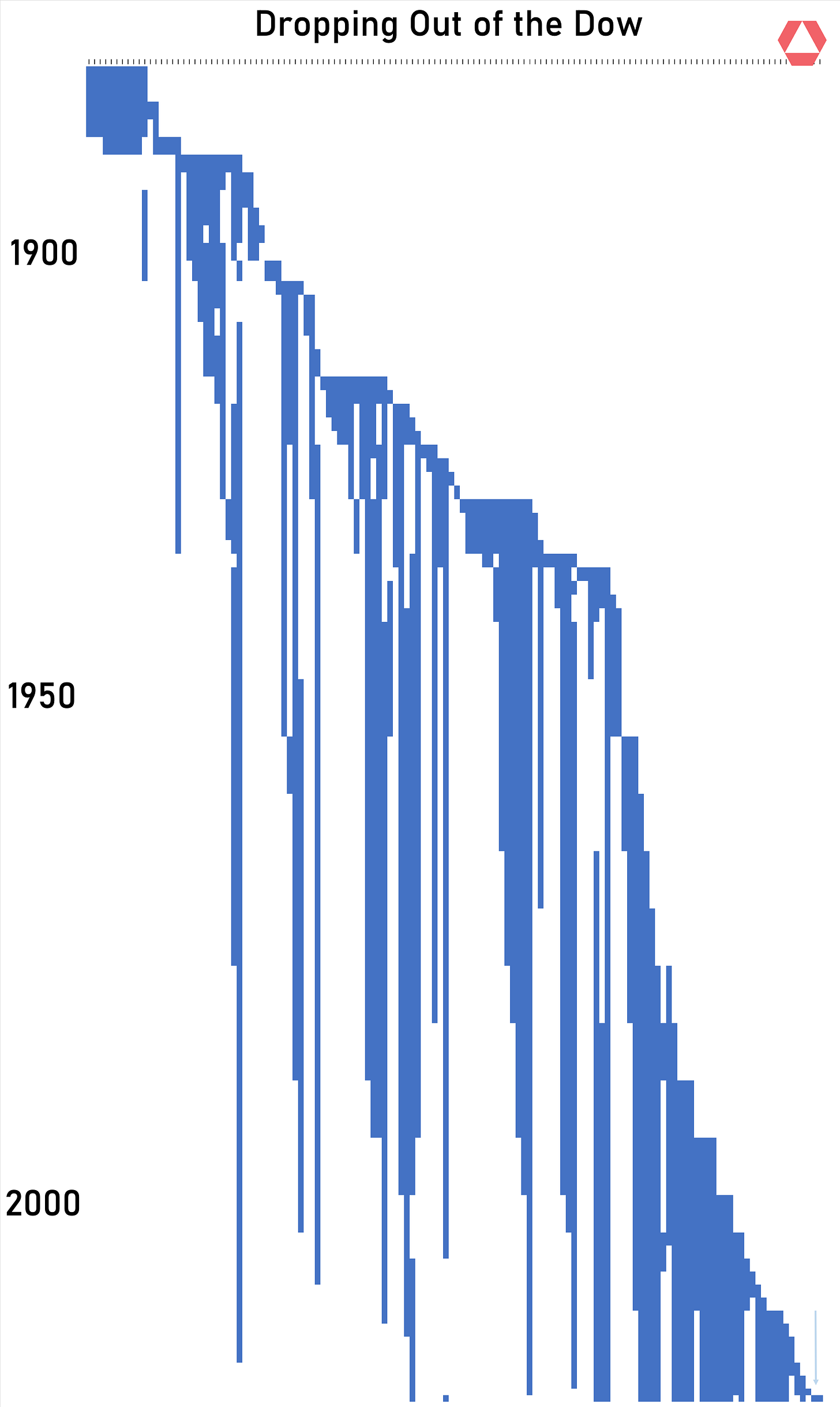

My friends at Rose created the graphic below to illustrate this. Each blue bar shows a company dropping out of the DJIA, so Chicago Gas and Light is one bar here.

The median time a company is in the average is 10 years. There are outliers, like Proctor and Gamble, that has been in the Dow since 1932! To go from the macro to micro, next week’s podcast features photographer Paul Fetters, someone who lived through the film disruption and, of course, the implosion of Kodak.

The Corporate Life Cycle

Companies are unstable because the economy shifts, technology evolves and companies need different types people at different stages of life. The mix is as unstable as a radioactive element. Academics study corporate failures the way the NTSB studies plane crashes. I’m partial to the work of Ichak Adizes who describes a lifecycle that runs from courtship and infancy to prime and then the fall, ending in recrimination, bureaucracy and death.

The evolution in the people required is curious. Given the (low) odds of success, you need to be a bit crazy to start a company. As Elon Musk said on his recent SNL appearance, “I reinvented electric cars and I’m also sending people to space in a rocket ship. Did you also think I’d be a chill normal dude?” If a business succeeds, it gains scale and complexity. This complexity creates a “moat” that protects the company and throws off cash flows. The administrative and people skills required to manage this complexity favor “chill” normal people. These people are both the glue that holds an organization together and unlikely to embrace disruptive ideas.

Implications

Given the above, a few guidelines I stick to that may help you as well.

1. I avoid concentrated investments in a company; I hold no more than 1% in a single stock.

2. I avoid stock market indexes (like the S&P 500). These indexes, particularly now, have a heavy weight to large, well established companies like Apple and Amazon whose greatness is already well recognized.

3. I don’t own long-term corporate debt, both because I suspect very low interest rates will rise and because the risk the company isn’t around is real.

4. When I was granted stock options (when I worked as a banker), I tried to liquidate them as fast as possible. Working at the bank already gave me plenty of exposure to the company. Of course, if you are at a start-up that you deem likely to undergo what Adizes describes as “infancy to prime,” stock options could be a rocket ship.

Instability is normal, unnerving and essential. The key question is always one of degree. The software entrepreneur I spoke to is out to take someone’s lunch, it’s just a question of whose.

If you want my current asset allocation (which changes a bit each week), give me a shout. The essence is long risky assets, long raw materials, short US bonds and long foreign bonds, among other positions.

I give a shout for the allocation

A shout is given.