“…the investor crowd often has superb intuitions about long-term events … these judgments should be respected and followed.”

Wealth, War and Wisdom, Barton Biggs, 2008

THIS IS NOT INVESTMENT ADVICE. INVESTING IS RISKY AND OFTEN PAINFUL. DO YOUR OWN RESEARCH.

I watched this week’s events through three lenses. These lenses are like being at the optometrist, keep flicking one on top of the other until the picture comes into focus.

Tech feast or famine. The current technology wave is feast or famine. I’ve noted this before and want to reiterate the point. Those on the right side of these cashflows will make so much money they won’t know what to do with it. Those people on the wrong side will be in a load of hurt. Winners are tech monopolies and the wave of companies enabling them or putting new AI technology to work via AI bots. Losers are the millions whose jobs will be impacted and the companies they work at. Winners are the US. Losers are Russia, Iran and probably China and Europe, too. AI is similar to past waves of tech change (canals, railways, engines, computers) but faster.

Government constraints. While the US is at the epicenter of the AI boom, the government faces significant constraints—a 6% budget deficit, above-target inflation, and a narrow Republican majority in Congress. If Trump cuts taxes, the bond market can sell off, crushing the stock market, and weakening the economy, meaning a tax cut can backfire. Similarly, internationally, he has less leverage than it appears. He wants to push Putin to a peace deal, but the US does little business with Russia. The US is about a $30 trillion economy and imports about $15 billion from Russia. The only real leverage he could exert would be significantly increasing US defense spending and shipping more arms and even advisors to Ukraine, which he is loath to do because of the deficit and his aversion to foreign conflicts. Note that yields on US bonds (and global bonds) have been rising since Trump pulled ahead in the polls.

A weakening of rule of law. In 1936, Hitler released Nazi zealots from prison who had been serving time for street violence. The parallels to this week in the US are obvious. Trump’s decision to free January 6 rioters was criticized by the Fraternal Order of Police and the International Association of Chiefs of Police. Trump’s message was clear—loyalty to Trump, not rule of law, is the way. Thus, we are seeing a breakdown of the rule of law. To be clear, Americans voted for this to happen, so there is nothing surreptitious. It just is.

I view any asset as a function of its sensitivity to these forces. For instance, the tech boom is bullish for certain stocks but bearish others. The constraints on the government are probably bearish bonds, absent a radical shift in spending, of which there is no evidence. The weakening of the rule of law is probably bearish the dollar, though that needs to be weighed against a global desire to invest in AI and potential tariffs. The last force—the breakdown of the rule of law--is the one I am least familiar with, so I dusted off a book on asset returns during 1930s and 1940s by Barton Biggs.

My takeaways are:

The longing for an authoritarian leader who will cut through social norms to establish “order” is a deep-seated human desire, particularly following periods of disruptive change. Many Germans found parts of the Nazi program extreme, but other parts of it an improvement from what had preceded. In Germany’s case what preceded it was losing a war, hyperinflation and a global depression. Hitler came to power in 1933, the nadir of the Depression. (Trump credits his victory to high grocery prices and the border, a modern version of chaos).

Stocks did well in fascist countries, until fascists began to lose, which took years. In Germany the key turning point was Stalingrad but before that stocks had a pretty good run. Note below that German stocks ripped higher as homicidal chaos was unleashed in Europe.

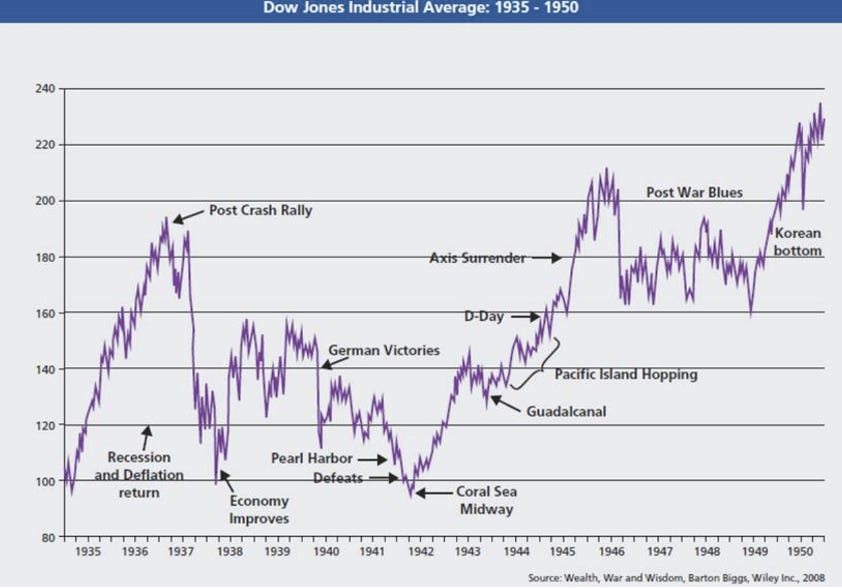

Valuation metrics like price-to-earnings ratios were less reliable than sentiment about whether the country was winning or losing. The US stock market was the mirror opposite of Germany, with stocks getting crushed as the US struggled and the end of the bear market that began in 1929 occurring in 1942 when the US began to triumph, at the time unexpectedly, over the Japanese.

High inflation is terrible for savers. Germany’s 1923 hyperinflation is the classic example, but in France and other countries inflation obliterated wealth. Moreover, when it comes to war, being on the losing side is devastating. The annualized real return of stocks in Germany from 1900-1949 was -1.9% and for bonds was -7.8%. In other words, you were wiped out.

Gold and property only offer theoretical protection. In practice, the most dear items were warm clothes and food, which required one trading gold on the black market, a dangerous endeavor. Property held its value over long periods of time but was often physically destroyed and sometimes recovered several generations later.

The best move was to get your money out of the country where rule of law fell apart and put it in the country (at the time the US) distant from the battle and with rule of law, though this took years to become clear. To what degree does rule of law break down? We need to observe and adjust as the evidence becomes clearer, one way or another.

Respect power. If you are a group targeted by fascists, take them at their word and get as far away as possible. In Germany, the targets were the Jews, homosexuals, gypsies, handicapped and opposition leaders. Today it is immigrants or trans people or possible political enemies.

Paul, I would not usually comment publicly on what you say, because, because…in the end I value your friendship more than your opinion. But in the end it was the heated debates we had together (and the family ties we also created together) that cemented our bond.

So…

Financially you are always theoretically wrong, but you win by exploiting niches and relentless analysis of small facts (who dared to go to small suburbs near Moscow? Who proposed me to tour third tier China cities together?)

Politically, you are always theoretically right, but you loose by exploiting niches…

Enough of running the paradox.

You are right on this one.

Curious your thoughts on deepseek and the implications if China manages to catch up in AI (a big if)