It Began in Sarajevo

Plus a lithium case study

To those of you that are new to these essays, welcome! You can find out more about Still Press and who I am here. This Substack grows through word of mouth, so high praise is when you forward this to your friends. To my existing readers: I said no more regular posts until 26 August…this is an irregular post! I’ll be back to schedule when I return to the US.

When I say “it”, I mean both modernity and post-truth, post-Cold War conflict. Sarajevo, where I spent a few days this week, is both where the triggering event of WW1 transpired and a key theater in the 1992-1995 Bosnian War. The fear in Sarajevo now is that if Putin begins to win in Ukraine, China will swiftly move on Taiwan and Serbia will attack Bosnia. Recent clashes between Serbs and Kosovaars amplified those fears.

Just as Covid brings the 1918 pandemic to life, Ukraine brings past conflicts to life. WW1 consumed about 40 million lives, 2% of the global population. The Bosnian War consumed about 100k lives, but came to a sudden end when NATO bombed Serb positions around Sarajevo. Given that Serbia is roughly the population of Massachusetts, NATO enjoyed overwhelming force. Looking at the pieces on the global chessboard today, the risks seem closer to WW1 while the post-truth narrative parallels the Bosnian War. Said another way, the stakes in Ukraine are much, much higher than just Ukraine.

The Birth of Modernity

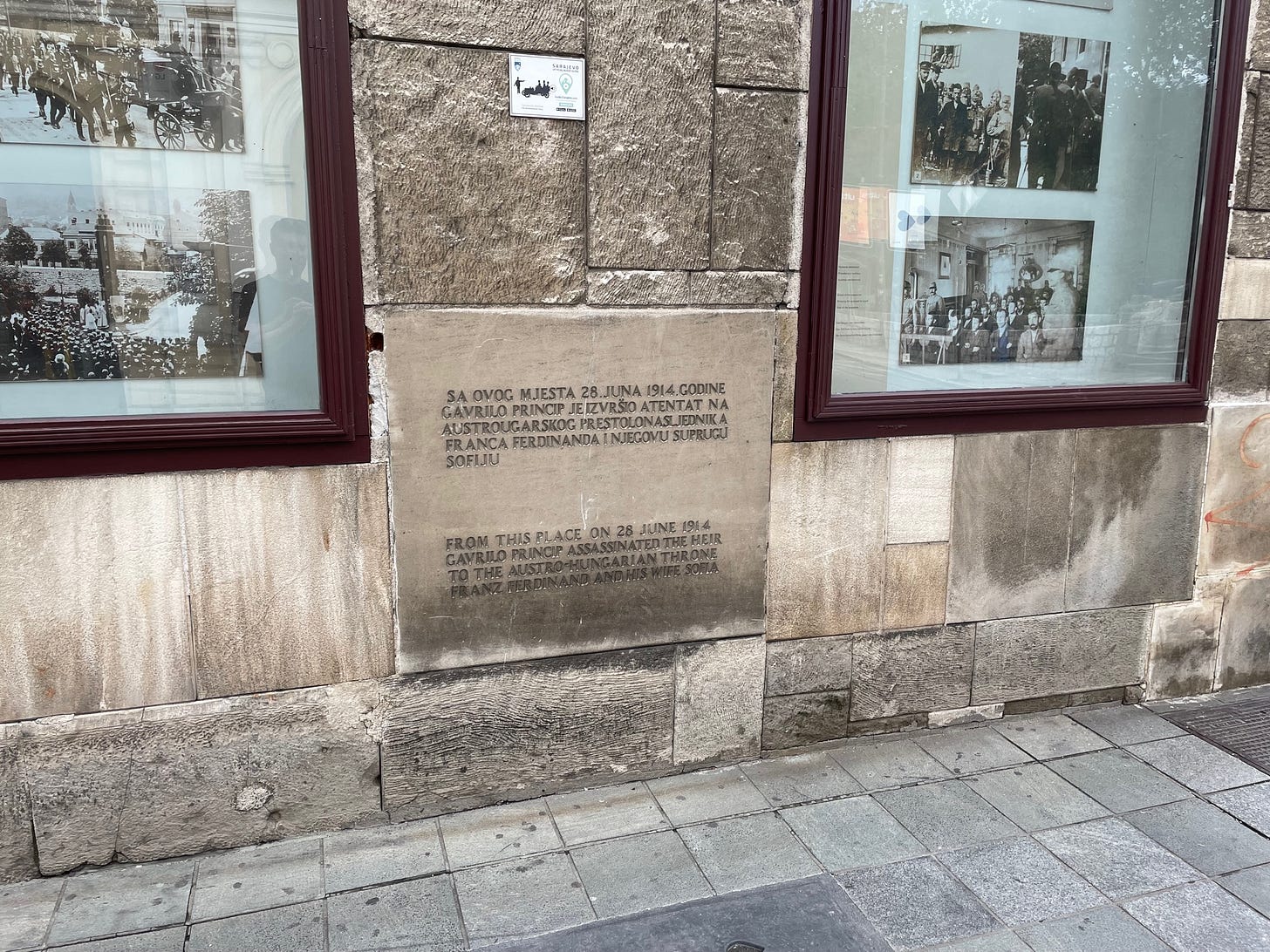

The spot where Archduke Ferdinand was assassinated is now a shabby, easily overlooked corner in downtown Sarajevo marked by the plaque below.

This is looking into downtown, the plaque is on the right.

Turning 180 degrees, I stared up at the verdant hills where the 1984 Winter Olympics were held and, in 1992, Serbian tanks encircled this city and pounded civilians with artillery and sniper fire. A section of downtown Sarajevo was re-named Sniper’s Alley.

The first I heard of Sarajevo was in a high school history course on the origins of German fascism. The story began with WW1, German hyper-inflation and aggrieved nationalism. With time, I came to see that one had to look even further back. In the 19th century, waves of technological change—canals, railroads, electricity—up-ended agriculturally-based social and economic rhythms, straining systems of government to adapt.

Social disruption goes hand-in-hand with improving living standards. The first railroad was built in Bosnia in 1872 and, like railroads everywhere, was a corridor of modernity. This week, asked about his thoughts on Uber, one interlocutor in Sarajevo told me, “oh, the taxi drivers here would beat the crap out of an Uber driver.” Economic shifts disrupt entrenched interests.

Via the Renaissance, Enlightenment and American and French Revolutions, Western political systems grudgingly evolved alongside disruptive technology. Not so much in what was known in my childhood as Yugoslavia.

On the day a Serb nationalist shot the Archduke, Bosnia was more or less lodged in a Middle Ages-era governing structure—a King ruled subjects. The Archduke, heir to the Astro-Hungarian throne and in formal military attire, was in Sarajevo to review the troops. Today, the Serb assassin is honored with a downtown Belgrade street in his name and Bosnia is still ruled by a potentate, this one appointed by the UN, whose power supersedes locally elected officials.

Countries, like people, fracture on fault lines. With better technology the fractures are more lethal—machine guns replace clubs, nukes replace machine guns. After WW1, Bosnia was absorbed into the newly created Kingdom of Yugoslavia, another feudal governing structure, even as West pushed for the creation of a supra-national governing authority, the League of Nations, a failed attempt to avert another world war.

The 1992-1995 War as Template

After WW2, Yugoslavia’s partisan hero Tito gradually seized control of an area that has since broken into seven different countries. Tito put a firm lid on internecine hatred, pushing it underground with Soviet ideology. Tito was more practical than ideological, however, adopting Soviet tactics where they served him well but shifting where they didn’t, like in economic policy. Soviet citizens regarded a trip to Yugoslavia as almost like going to Paris. The scope of Tito’s accomplishment was hard to understand until the war broke out in 1992.

Tito died in 1980, just nine years before the Berlin Wall fell. Two years later, 1991, the most wealthy, Western parts of Yugoslavia bailed on the Yugoslavia project. Slovenia (Melania Trump’s hometown) is nestled next to Italy and taking orders from backwards Belgrade seemed absurd. Croatia owns the prime real estate along the Adriatic and correctly saw that on their own they could become a tourist Mecca, the Amalfi Coast at a fraction the price.

Bosnia is roughly 50% muslim, 50% Christian, split between Orthodox (Serb) and Catholic (Croat). When the 99% of those Bosnians who voted (the Serbs boycotted), to become independent of Serbia, the Serbian penalty administered, as in efforts to scale the Berlin Wall, was death.

When the Bosnian war kicked into its most lethal phase, I read the news in a graduate school library and had trouble making sense of what was going on. Driving to Sarajevo up a windy road dotted with newly built (Saudi and Malaysia funding) mosques helped put things into perspective. The Serbs are a Russian client-state united by a history in authoritarian governing structures, similar language and religion and an ancient suspicion of Muslim populations.