The Cacophony Economy

The TV/Book/News Pipes

A business has three moving parts—content, distribution and financing. Since the advent of modern capitalism about 250 years ago, there have been a series of battles over who controls distribution. Today, this fight centers on information. What’s referred to as the “creator economy” is in fact a cacophony economy. Anyone can post anything, thus the cacophony. What we see, however, is a function of algos that feed off emotions like anger and lust or something quite old-school, ad spend.

Old Industrial Corridors

Before the Industrial Revolution. living standards were not that much different than they had been in the Roman Empire. The first meaningful shift in distribution was the creation of canals. Roads made of water transported wheat and coal from where they were produced to where people needed them, leading the cost of coal and wheat to plummet and the fortunes of both those who owned the canals and initial investors to soar.1

Capitalism is an instability machine. Technology evolves, creating vulnerabilities in old systems. Railroads and train tracks obliterated the canal business. The trains carried similar things but they had structural advantages—like not freezing in the winter—and were faster. Canals and their stock holders got crushed, and families like the Vanderbilts, the Goulds and the Harrimans became wildly wealthy. Their mansions outlive them and are now museums in coastal Rhode Island.

Cars and airplanes disrupted trains. Over a few centuries, new inventions didn’t eliminate the old ones, they grew on top of them. Part of the war in Ukraine is a fight over old fashioned pipes carrying natural gas or ports exporting wheat. The question is always who gets control and the price for access, which is a function of the relative power of those who offer content, distribution and finance.

New Industrial Corridors

Today’s information distribution is radically different from the previous. When I grew up in 1970s Washington, there were three meaningful information pipes—books, TV and newspaper. In my hometown., the top companies in these spaces were Farrar Strauss and Giroux (books), CBS News and The Washington Post.

These companies were both profitable and influential. When Russian dissident Alexander Solzhenitsyn published books via Farrar Strauss it was disruptive enough that he was thrown out of the Soviet Union and perhaps played a small role in his country’s collapse. When Walter Cronkite voiced skepticism over the Vietnam War, he helped end it. When The Post’s Woodard and Bernstein went after President Nixon, he resigned.

Ownership was concentrated, content highly curated (lots of gatekeepers) and distribution a patchwork. Owners like Robert Strauss, William Paley (CBS) and Katherine Graham (Washington Post) were not as wealthy as the Vanderbilts (hundreds of millions versus billions), but they were more influential. To get a book published, for instance, a writer needed to attract an agent, who then struck a deal with a publisher, which distributed through independent book stores, like Kramer’s in D.C. or The Strand in New York. The Post controlled Washington, but had almost no distribution beyond.

The revenue model of CBS and The Post was largely driven by advertising. Farrar Strauss had monopoly control over cultural icons and charged a premium for access. The publisher had more power than the distributor. The distribution networks were funded by equity and debt but the PE, or price paid for the earnings, for these media stocks was never that high because the potential distribution was structurally limited. The Post, for instance, was not selling in Texas.

New Industrial Information Pipes

The internet created a new pipe, doing to the old model what railroads did to canals. It has happened fast. The internet simultaneously created unprecedented scale, no gate keepers, and a rapid shift in cash flows that favors distributors relative to those that provide content or finance. Armies of people—book agents, advertising salespeople, copy editors, reporters—saw their cash flows decline, while others—software engineers, computer scientists, venture capitalists and above all entrepreneurs—saw theirs soar.

Jeff Bezos (Amazon), Reed Hastings (Netflix) and Jack Dorsey (Twitter) either understood what was going on faster than others or were lucky or both. They are the modern-day Vanderbilts, billionaires all, with Bezos the second richest man in the world. They wield more power than Katherine Graham, William Paley and Roger Strauss combined but outsource content judgement to algorithms that, to date, favor anger and lust more than logic or people who pay for placement.

Amazon is an interesting case study because their control of distribution channels, like books, is so dominant. Bezos financed unprecedented scale via stock investors willing to pay a very high price (the PE) for the promise of future profits, similar to the ardor once elicited by canals and railroads. Bezos uses distribution to control suppliers by forcing them to sell at lower prices than they did in the past. This eviscerates legacy business models, offers consumers lower prices, and, because consumers like low prices, helps insulate Amazon from regulatory action.

The book above is from the 1970s. The inflation adjusted price today would be $70. The Kindle gained traction around 2010. Today, Amazon carry tens of millions of books, making the local book store look as dated as a typewriter and driving down prices closer to $10.

“For the big book publishers, Amazon’s dawning monopoly in e-books was terrifying. As suppliers had learned … no matter the category, Amazon wield its market power neither lightly or gracefully, employing every bit of leverage to improve its margins…,” wrote Brad Stone in The Everything Store.

By 2013, two of the most storied publishers, Penguin and Random House, merged. If the Justice Department allows it, a proposed merger of Simon and Schuster and Random House, traditionally published books will come from just four companies: Bertelesman, News Corp, Lagarderie Group and Holtzbrick. Weak profits forced consolidation (a more detailed table is Subscriber-only).

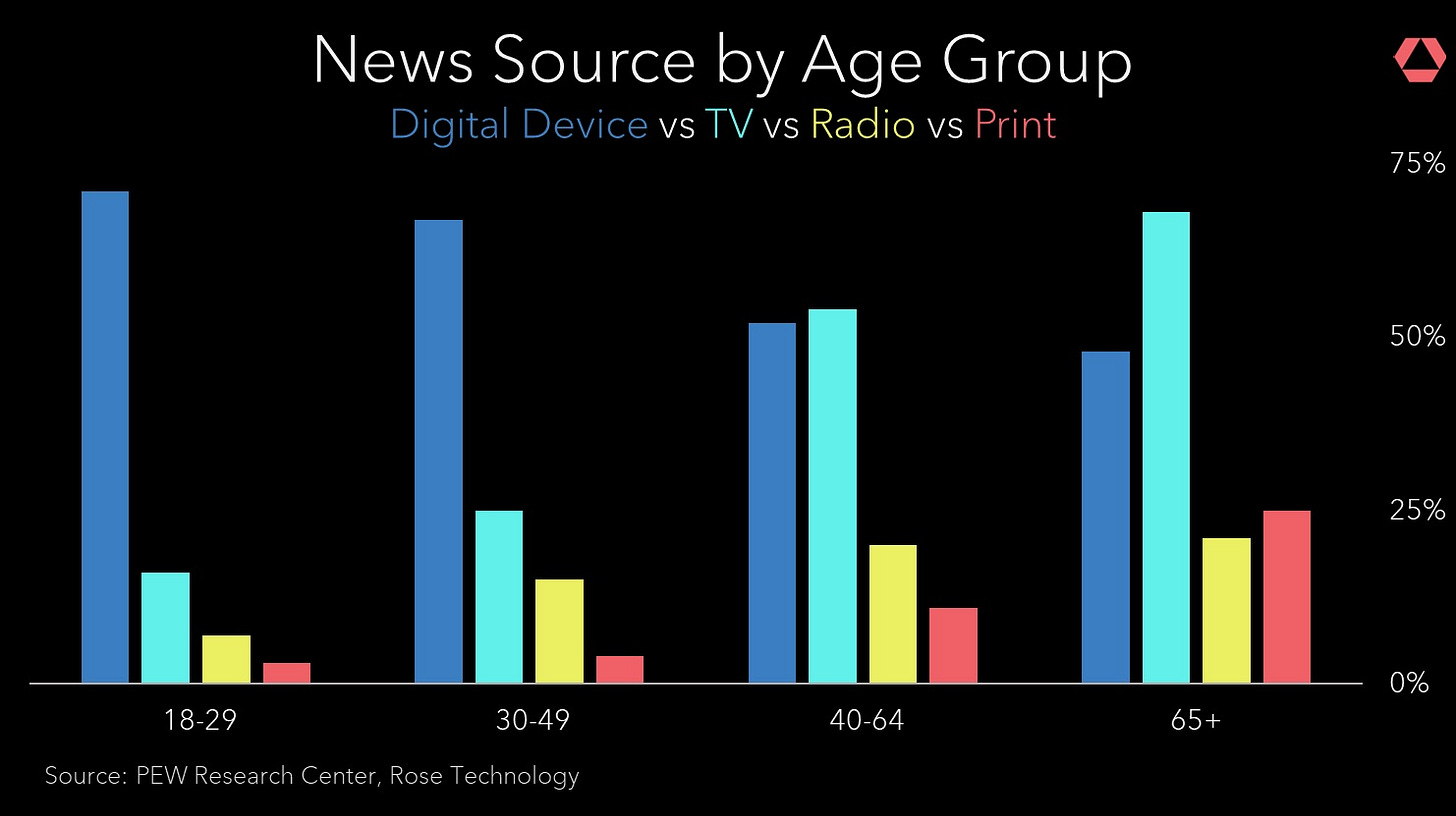

The internet wreaked similar havoc in traditional newspapers and TV by crushing ad revenue. About 30% of US newspapers have died, some of them well over 100 years old.2 The young barely watch TV (as the Rose chart below shows).3 More people follow Justin Bieber (114 million Twitter followers) than watch Anderson Cooper (about 500k viewers).4 Trump understood this very well.

Going Forward

Going forward, I suspect tightening financial conditions