To those of you that have recently signed up, welcome! My name is Paul and I help you follow the money to put current issues into perspective. For more about what these essays are about, click here. I’ve shared the rubric that organizes these posts here. Today’s note is about a) saving money b) stocks and c) Russia and other countries known as “emerging markets.” If someone forwarded this to you, click below to subscribe.

Vladimir Putin wants respect. He might feel he needs to invade Ukraine get it, which is why you are seeing stories about Russian troops massing on Ukraine’s border. Unpredictability may be useful in geopolitics, but it is terrible for investment. The poor long-term return on Russian stocks is a case study in a) how disappointing emerging market or “EM” investing has been1 and b) why rule of law and wealth are related.

My Early Lesson

The term “emerging markets,” or EM, was coined in 1981 by Antoine van Agtmael at the World Bank. China had recently emerged from Maoism. The hope was that foreign investors could earn attractive returns by directing their savings to EM entrepreneurs hungry for capital. The Berlin Wall fell eight years later.

The reality was something else, as I saw first hand. In 1997, I was invited to a series of meetings with Mikhail Khodorkovsky, then worth $15 billion and Russia’s richest man. Like most billionaires, he held a high opinion of himself. Putin became President in 2000 and Khodorkovsky dared to criticize the Kremlin. He was arrested in 2003, charged with fraud and served 10 years. I saw grim pictures of him behind bars and could barely believe it was the same guy. Wealth is always unstable, particularly in EM.

There is a Russian saying that “the severity of our laws is compensated by the rarity of their enforcement.” In many EM countries, the rules are fluid and often unwritten, which means everyone can be prosecuted if the government choses to do so. Jack Ma, once China’s richest man, was dethroned after criticizing the government, just like Khodorkovsky (though Ma did not go to prison). It is hard enough to make money investing with relatively predictable politics.

The Case at Hand

Today, if you lend a dollar to the US government for ten-years you earn 1.6%. Russia gives you 8.3%. This pricing is matched asset by asset. A share of JP Morgan is more expensive and pays a much lower dividend than the Russian equivalent, Sberbank. Why?

The geeky answer is the market is pricing in a substantial decline in the Russian ruble.2 (This is an issue finance experts talk about a lot, but I have relegated it to a footnote because I think most readers don’t want that level of detail). The conceptual answer is the market is pricing a system that is medieval. By medieval I mean a system ruled by a King, where palace rivals are poisoned, and borders are determined by relative military advantage. It’s like Shakespeare, but with the internet and nuclear weapons.

There are lots of places with disputed borders like the one between Russia and Ukraine. If one country begins to forcibly shift a border, others will want the same, opening up potential chaos. In July, Putin published an essay called “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians.” Much of the essay is abstruse (“…it ended with the Truce of Andrusovo in 1667”). Putin claims Ukraine and Russia are “essentially the same historical and spiritual place.” If that’s what he thinks, then the border, which the Ukrainians are defending to the death, might not matter much to Putin.

Putin might not to invade. If he doesn’t invade, Russian assets probably go up. Invading is expensive, will be unpopular if Russian soldiers start dying and jeopardizes a natural gas pipeline deal Russia is trying to close with Germany. At the same time, Putin believes the US is weak, particularly after Afghanistan. The answer is unknowable, which is why investors are stepping away. This same type of dynamic has unfolded again and again, both in Russia and other EMs.

Investors often get wiped out via the currency. If you own Russian stocks and the Russian ruble falls, your own wealth, measured in dollars, falls. The Russian ruble has yet to recover from the invasion of Crimea … seven years ago. (Though the actual return of investors looks a bit better again due to the geeky math in the footnote). The chart below showing Russian GDP measured in US dollar’s, with a comparison to a neighbor, Poland. Said differently, Russian GDP would be $2.4 trillion higher if they had not invaded.3

A 30 Year Underperformance … or a US Bubble?

By all classic measures, the ruble is undervalued. Many other EM currencies also look “cheap.” Yet, if Russia invades Ukraine, the ruble will become even more undervalued as foreign investors back away and domestic investors panic. While Russian stocks have earned solid returns over the last few years, they are extremely volatile, which means investors can not hold many of them in their portfolio without their performance becoming disproportionate.

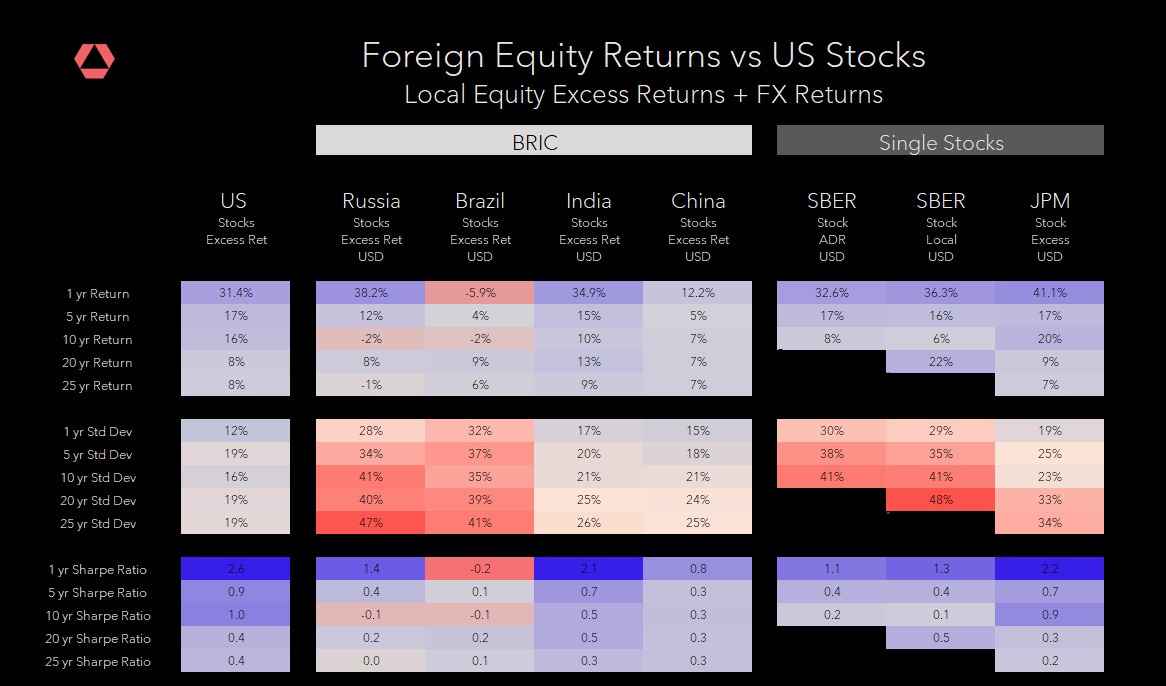

The chart below from Rose is both a wall of numbers and critical for any finance geek. It shows the return and risk of emerging market assets. Divide one (return) by the other (risk) and you get the ratio which is like the miles per gallon for an investment. What is shows is that the miles per gallon for Russian assets are low, largely because the volatility is so high. In part, this is because Russia’s oil-dependent economy is very volatile but it is also likely because of political risk.

To be sure, not all emerging markets countries are not the same. Brazil and India are what The Economist Intelligence Unit labels flawed democracies, like the US. China and Russia are authoritarian. Russia and Brazil export commodities, China and India import them. It’s also worth noting that US is becoming more unstable, which The Economist ratings show. The fact that emerging markets are disappointing and the US is both expensive and increasingly unstable perhaps explains the why some (not me) are enthralled with bitcoin and Ethereum.

I’ll share my asset allocation with subscribers next month. I hold less EM now than I did at the beginning of the year and have tilted more into places I’d once avoided, like Europe and Japan. My experience in Russia, including the most recent one, helps explain why. I’m also now more interested in countries on the periphery like Canada, Australia, Norway and Sweden. As I’ve said many times, wealth is unstable and you need to be attentive to both earn it and hold on to it.

If anything I wrote is unclear, write me at paul@paulpodolsky.com. For more access, become a subscriber or a sponsor. On Wednesday, we (the Still Press team) release our next podcast, a conversation with Tamara Chubinidze, the founder and owner of the Georgian resteraunt Chama Mama. We’ve had guests on from Russia, China and France and I’d like to continue to pull in stories from around the world. Her’s is a fascinating one.

The shorter-term (5 year) return on Russian assets has been pretty good.

The ruble is discounted to decline about 75% over the next 10 years. The forward price of the ruble is a function of the local interest rate, 7.5%, relative to the US interest rate, roughly 0, meaning the ruble is discounted to fall 7.5% over the next 12 months. The interest rate pricing (which drives this forward discounted rate) is about the same at 10 years. This means if the ruble only falls 10% over the next 10 years, an investor would make 60%. While Russian assets have underperformed over the long-term they have outperformed on a shorter-term (5 year) basis, in part due to a compression of risk premiums after the invasion.